To read this article in Spanish click here

On a hazy day in November, Hardeep Singh received a text message from the COVID-19 testing system at Foster Farms poultry company saying that his mother had tested positive for the coronavirus.

He got the alert because his mother, a 63-year-old line worker at one of the company’s meat-packing plants in California’s San Joaquin Valley, doesn’t speak English and doesn’t own a smartphone.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Singh couldn’t reach her as she continued to handle chicken parts alongside her co-workers. Her supervisors didn’t tell her, either. In fact, they assigned her more shifts for the week.

Singh broke the news to her that evening, and convinced her not to return to work, where she might spread the infection to others. But he couldn’t reach anyone at the company for another five days, to ask whether she qualified for paid time off while she isolated.

Singh’s mother ended up being among the more than 400 employees at the plant who were diagnosed with COVID-19 last year, and one of about 90,000 cases linked to food-production facilities and farm work across the United States. Because the sector feeds Americans and powers part of the US economy, agricultural workers such as Singh’s mother have been considered essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That important role comes at a cost. One study found that food and agricultural workers in California had an almost 40% increased risk of dying last year, compared with the state’s general population. And within that imbalance lies another contrast. Latinx food and agriculture workers experienced a nearly 60% increase in deaths compared with previous years; the increase for white workers was just 16%.

The reasons for such disparities, say public-health researchers, include discrimination, low wages, limited labour protections and inadequate access to health care, affordable housing and education. These are some of the ‘social determinants of health’, a concept that has been around for at least 150 years, but which has gained recognition during the pandemic.

Credit: Nature

The phrase was on the lips of Anthony Fauci, the highest-ranking infectious-disease scientist in the US government, as he explained why Black, Latinx and Indigenous people have been affected by COVID-19 much more than have white people in the United States. The concept has also attracted infusions of grant money from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US National Institutes of Health. Yet although scholarship on the social determinants of health has been growing for decades, real moves to fix the underlying problems are complex, politically fraught and, as a consequence, rare.

The pace of change looks particularly stagnant when compared with advances in infectious-disease biology, in which researchers have isolated pathogens and created life-saving therapies and vaccines to stop them.

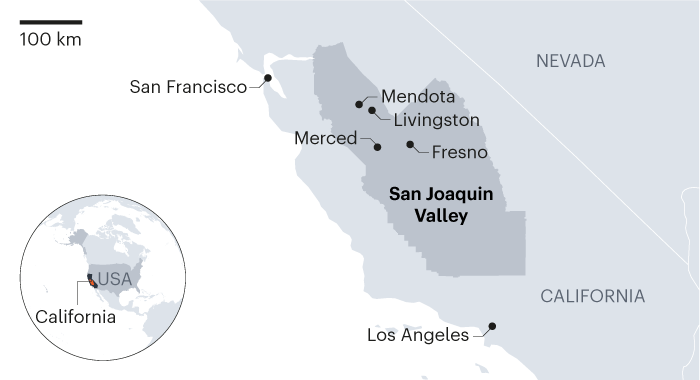

To understand what makes confronting the social determinants of health so hard, I investigated the tumultuous coronavirus response in the San Joaquin Valley, where hundreds of thousands of agriculture workers reside. Most of them were born outside the United States, and many lack legal residency, meaning they have limited access to social services, such as unemployment benefits or health care, despite paying taxes.

The valley is one of the richest agricultural regions in the world, and simultaneously has one of the highest poverty rates in the United States. During the pandemic, it has provided a clear example of how inequality renders some groups of people much more vulnerable to disease.

“We call them essential, but they’re considered expendable,” says Singh, himself a medical student pursuing a dual degree in public health. He asked for his name to be changed because of concerns that speaking out might cost family members their jobs.

As COVID-19 devastated disenfranchised communities in the San Joaquin Valley (see map), grass-roots organizations joined with local researchers to provide help. They’ve organized testing drives and educated communities about the disease and vaccines. But much of their work falls outside medical care, such as advocating for labour rights and subsidies for housing.

These types of social and economic intervention are what’s really needed to address health disparities, but many academics and health officials are reluctant to push for such measures publicly, says Mary Bassett, an epidemiologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who is a former commissioner of New York City’s Department of Health. That reticence needs to change, she says. “We need to be more outspoken about things that aren’t in our lane.”

Bassett is one of a growing number of researchers who are getting political, and who hope that COVID-19 will be a catalyst for change in the field. “The pandemic has turned up the dial, and to me it brings out a sense of urgency,” says Arrianna Marie Planey, a medical geographer at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Not content with simply identifying the social determinants of health, she says public-health researchers should be doing more to address them.

“I see a study saying COVID is higher in farmworkers, and I’m not interested—I want to know what’s next.”

An unhealthy past

A Prussian doctor, Rudolf Virchow, described the social determinants of health long before the phrase was coined. In the mid-1800s, he began a government-commissioned investigation into outbreaks of typhus in Upper Silesia, a coal-rich region in what is now Poland.

Virchow documented hunger, illiteracy, poverty and depression among Silesians, and concluded that the root of the problem lay in their exploitation. “The plutocracy, which draw very large amounts from the Upper Silesian mines, did not recognize Upper Silesians as human beings, but only as tools,” he wrote in his 1848 report on the typhus epidemic.

Virchow’s radical solution was that “the worker must have part in the yield of the whole”.

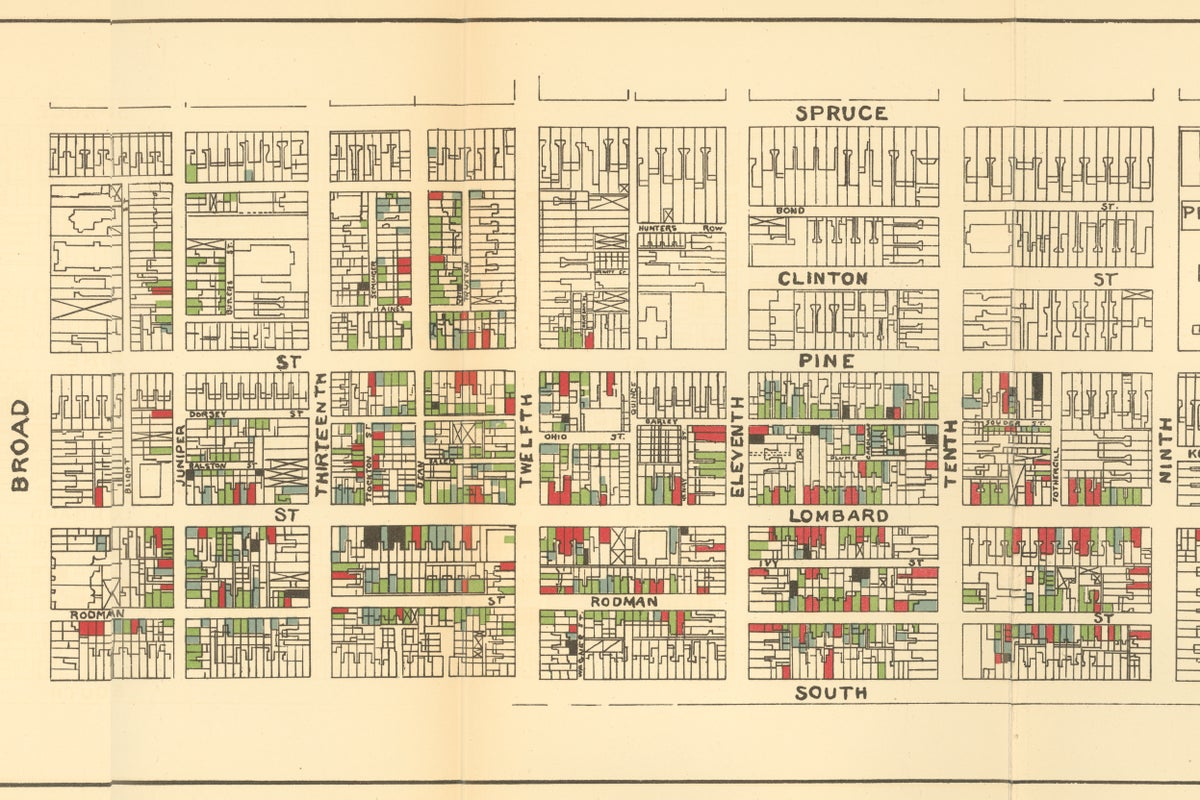

The US sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois reached similar conclusions at the turn of the twentieth century, in a body of work that powerfully refuted eugenicist hypotheses suggesting that Black people died earlier in the United States because of their biological make-up and supposed unsanitary behaviours. Du Bois intensively surveyed people across Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and found that mortality rates were similar across races in city wards that ranked well on metrics for housing, education, occupational status and other variables.

At the turn of the twentieth century, sociologist W. E. B. DuBois explored the health and living conditions of Black people in Philadelphia in exquisite detail.

Credit: University Archives Image Collection, University of Pennsylvania

Higher death rates among Black people were linked to wards that were worse off by these metrics. His conclusion: the conditions of people’s lives mattered, not the colour of their skin.

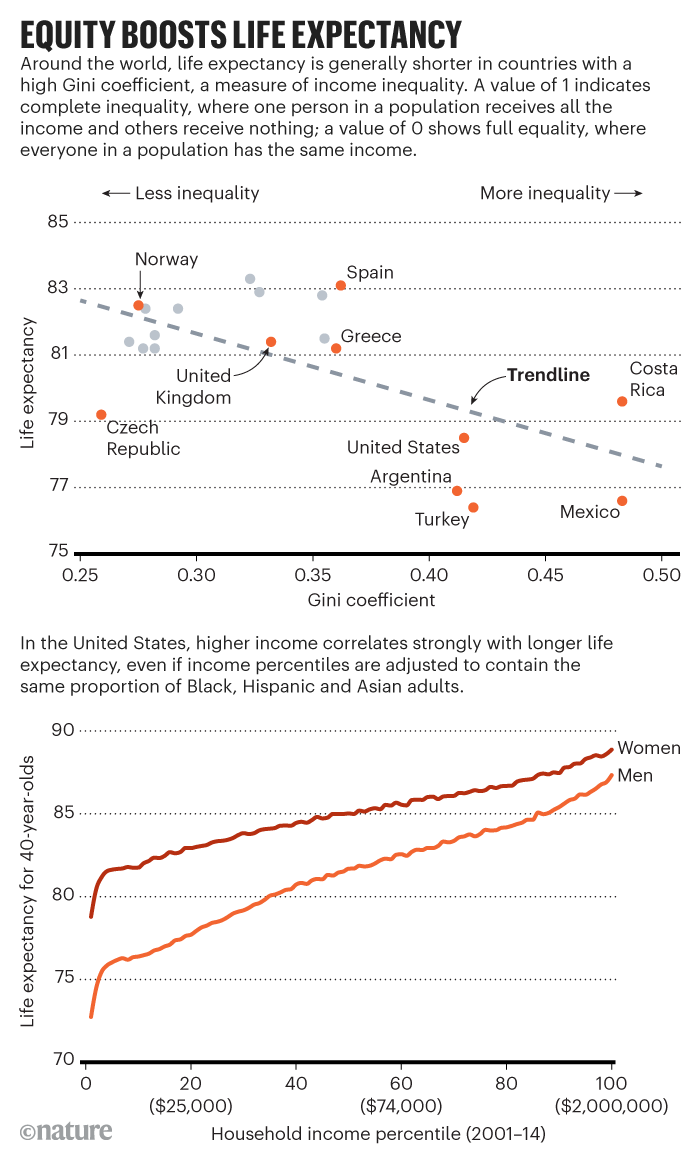

Despite a steady drumbeat of studies over the next century calling out the social and economic roots of poor health (see ‘Equity boosts life expectancy’), policies have rarely changed in response, says epidemiologist Michael Marmot, director of the Institute of Health Equity at University College London.

For example, a major investigation in the United Kingdom in 1980 concluded that, to remedy disease disparities, the government needed to put more money into public education, public health and social services, while raising taxes on the wealthy. The Black Report, named after Douglas Black—its lead author and an early supporter of the UK national health system—made waves in health-policy circles, resulting in the World Health Organization leading an assessment of health disparities in a dozen countries.

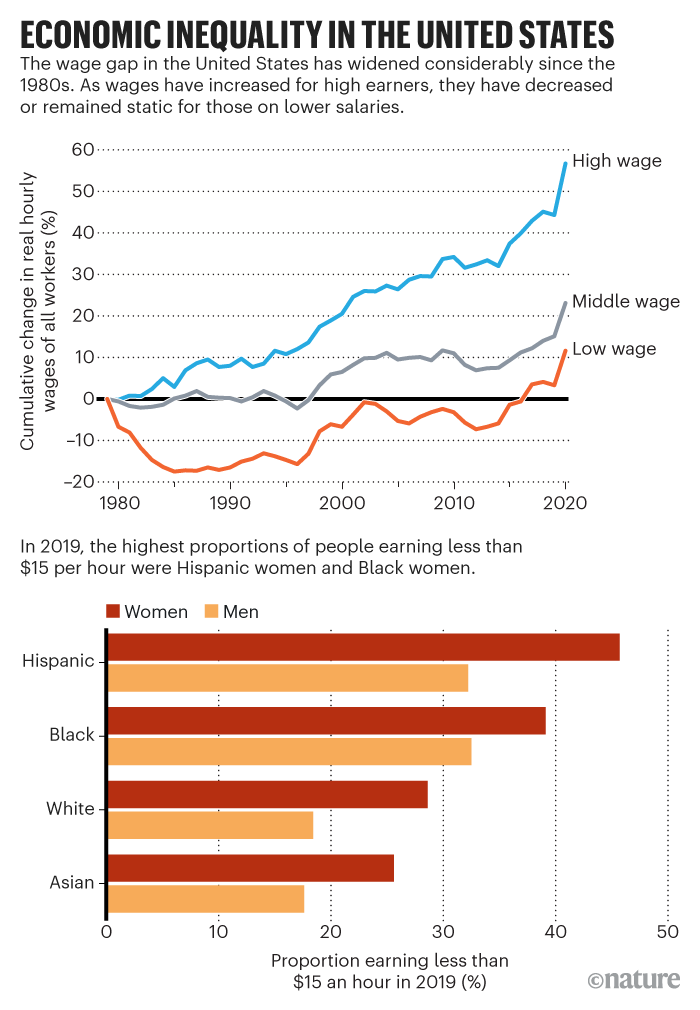

But the recommendations gained no traction with leaders at the time. UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher and US president Ronald Reagan, for example, slashed public expenditure, cut taxes for the rich and deregulated companies to boost their countries’ faltering economies. The gross domestic product of both countries rose, but so did poverty and economic inequality (see ‘Economic inequality in the United States’).

Many of the trends set in place during the 1980s continued, even as ruling political parties changed. US president Bill Clinton’s administration, for example, made welfare harder to receive. And as the gap between the rich and poor grew, so did health disparities.

By 2014, the wealthiest 1% of men in the United States were living 15 years longer, on average, than the poorest 1% of men. Those inequalities are poised to grow, predicts a report in The Lancet in February. The report notes that former US president Donald Trump legislated a trillion-dollar tax cut for corporations and high-income individuals, while weakening labour protections, health-care coverage and environmental regulations.

Credit: Nature

Bassett, an author on the Lancet report, says, “We had every reason to prepare ourselves for a bad epidemic when COVID reached us because this country is full of holes.” She lists several: it lacks universal health coverage and mandatory paid sick leave; it has a minimum wage that is below a living wage; and it relies on an immigrant workforce, many of whom lack legal status.

Ground truth

In the bone-dry grape fields of the San Joaquin Valley, farmworkers clip and bag bunches of grapes at a furious speed—they’re paid by the package. A farmworker whose eyes peek out above a dirt-caked bandana doesn’t stop moving as I ask, through a translator, whether she would get tested for the coronavirus if the owner of the farm provided tests.

No, she whispers, because if it were positive, she couldn’t afford to miss work. Another farmworker, a broad-shouldered man with calloused hands, echoes the sentiment. “Farmworkers don’t stop for a pandemic,” he says. “We keep working.”

Both requested anonymity because they are undocumented immigrants from Mexico.

I drive past tidy rows of nectarine, pomegranate and almond trees, on the way to a melon-packing plant in the city of Mendota, where hundreds of farmworkers queue in their cars alongside a road. They’re waiting for boxes filled with vegetables and starches.

Food drives such as this occur regularly in California, to assist the estimated 800,000 farmworkers in the state who live far below the poverty line. On this sweltering afternoon, free COVID-19 tests are available in the car park across from the food distribution site. But that area remains vacant.

About a dozen farmworkers waiting for food echo what those in the grape fields had told me: a positive test threatens their survival. In a beaten-up minivan, a woman with blonde hair grips her steering wheel and confesses, “I’m very frustrated.” She had COVID-19 a few months earlier, but returned to pick lettuces as soon as she felt well enough to stand. Her “bones hurt”, she says, but she hid the pain from her supervisor out of fear that she might be fired. “Essential workers are forgotten,” she says, before inching forwards in line.

Similar fears and frustrations had flooded the Facebook inbox of Tania Pacheco-Werner, a medical sociologist and co-director of the Central Valley Health Policy Institute at California State University in Fresno. Many farmworkers know of Pacheco because she immigrated to the valley from Mexico City as a child with her parents, who worked in the fields.

Pacheco observed the contrast between what public-health officials were recommending, and what agriculture workers can realistically do. For example, the CDC said people should physically distance, but that is often impossible in food-processing plants or in the cars that people share to get to work.

Such realities meant that deaths mounted for Black and Hispanic people in the United States, who are more likely than white people to hold low-paying jobs that cannot be performed at home.

With people she knew in dire straits, Pacheco wasn’t content to study COVID-19 disparities. She got in touch with grass-roots organizations in Fresno—the most populous city in the valley—and learnt that they had similar concerns.

By May, around a dozen groups, such as the African American Coalition, the Immigrant Refugee Coalition and the Jakara Movement (representing immigrants from Punjab state in India), were lobbying Fresno’s leaders for interventions tailored to the needs of their communities. They warned that the coronavirus response would fail without their help, because disenfranchised groups trusted them—not the government.

This was particularly true among undocumented immigrants, who had faced increasing discrimination since the election of Trump in 2016. Trump repeatedly denigrated Mexicans as criminals, and passed policies to increase deportations.

Farmworkers told me they watched videos of raids by US immigration and customs officers in fear. It made them as wary of public-health officers as they were of the police. “When you realize how screwed people get here,” Pacheco says, “mistrust begins to make sense.”

For the first few months, Pacheco and her colleagues say that the Fresno county government, led by a predominantly white board of supervisors, ignored their requests to enforce safer conditions on farms, food-packing plants and warehouses, or to provide paid sick leave and other financial assistance for essential workers.

The board also resisted some public-health measures aimed at reducing the spread of the virus. In May, for example, it revised the wording on masking guidance from the Fresno county health department and publicly undermined the messaging.

Credit: Nature

In a statement released just after the original guidance, a Fresno county spokesperson wrote, “The updated Health Officer Order is a recommendation, NOT a mandate.”

As the summer of 2020 wore on, the situation grew contentious. At public meetings with the board of supervisors, some people protested against business closures, whereas others accused leaders of failing to protect people in poverty who don’t have the freedom to decide what risks they can take. “It’s not a lifestyle choice!” one Fresno resident shouted. “They work in packing houses, they work in the fields!”

Meanwhile, Fresno’s public-health department found itself serving as a mediator between community organizations and agriculture companies. The tension between the two groups comes through in e-mails obtained through a national COVID-19 documentation project run by Columbia University in New York City.

In a message from July, for example, Tom Fuller at the health department wrote to his colleagues about his conversations with farm and food-plant owners: “I have detected an undercurrent of suspicion and perhaps resistance towards some of the groups that have identified themselves as wanting to be part of the County response to the pandemic.”

Fresno’s health department had little ability to fight the board’s decisions, because its jurisdiction is limited to a handful of measures, such as immunizations and disease surveillance. Plus, says Miguel Arias, a member of Fresno’s city council, the board dictates the health department’s leadership and budget.

“The department of health is as strong as the board of supervisors allows it to be,” Arias explains. Similar power dynamics played out across the United States, and were exacerbated by protests against coronavirus measures. At least 181 public-health officials resigned, retired or were fired last year, and many of them had faced harassment from the public for doing their jobs, according to an investigation by Kaiser Health News and the Associated Press.

Arias, too, was threatened. He and other city-council members pushed the board to expand testing on farms, and couple it with paid sick leave. But his confrontational approach got him into trouble.

“One of the supervisors said to me, ‘Stay in your lane—we aren’t going to disrupt the agriculture industry at the peak of harvest’,” he recalls. On another occasion, men associated with the Proud Boys, a violent, far-right organization, showed up at Arias’s home to confront him.

Buddy Mendes, the chair of the board of supervisors last year, refutes claims that they didn’t push for testing on farms because it would be bad for business. Rather, he says, the board had concerns about the type of rapid diagnostic tests being proposed. And he says the board wasn’t ignoring community groups. “It took until August to get the scope of works prepared, and contracts in place.”

Indeed, the community organizations found their footing in August, just as the outbreak in the San Joaquin Valley exploded. California governor Gavin Newsom approved US$52 million to fund the coronavirus response in the region, and specified that it should target the disproportionate number of Hispanic people who were testing positive for the coronavirus—they accounted for nearly 60% of cases.

It was during this surge that the board gave $8.5 million to the community organizations, after they partnered with doctors and researchers from the Fresno campus of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), to form the Fresno COVID-19 Equity Project. A few weeks later, the team converted an austere church belonging to the Fresno Interdenominational Refugee Ministries into a coronavirus testing site.

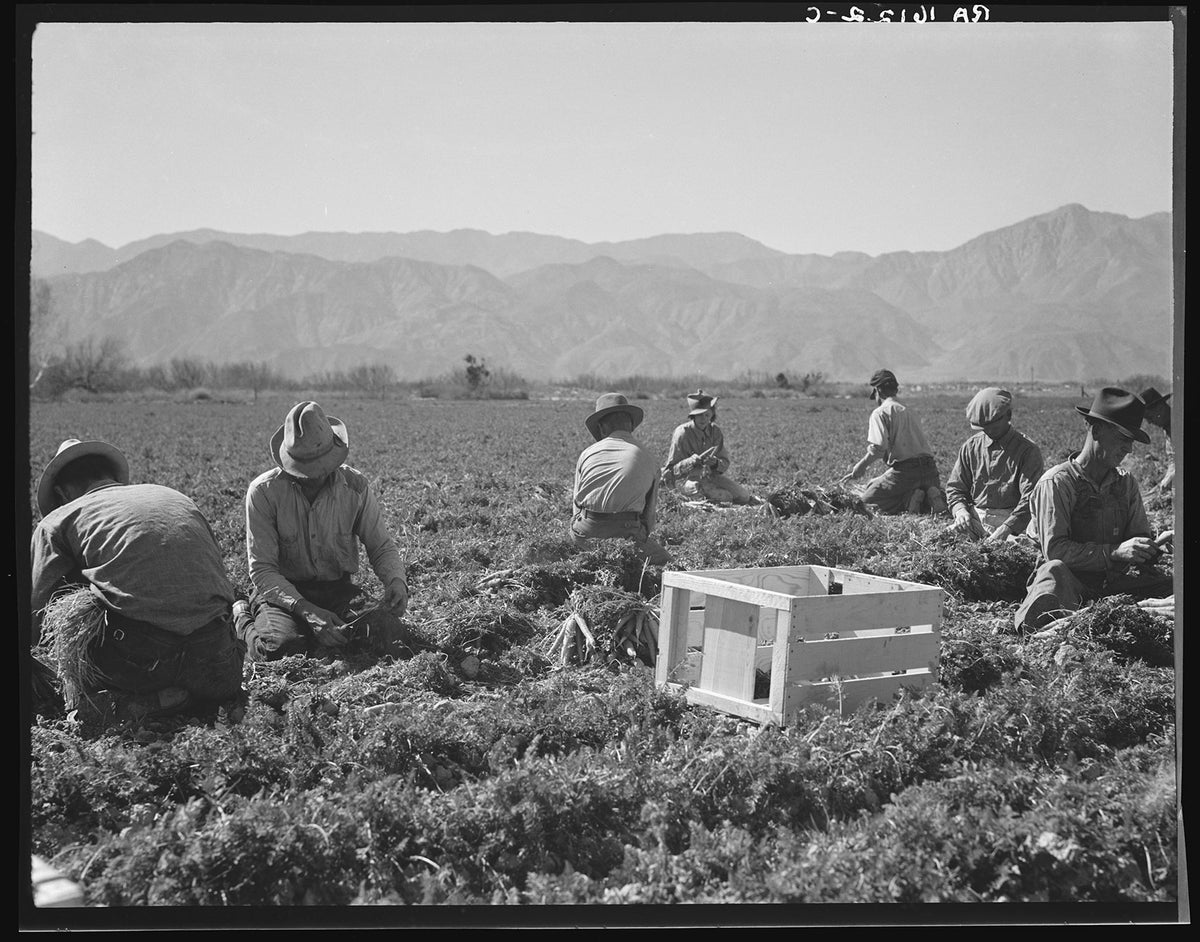

Immigrants from Mexico, dressed to protect themselves from the sun, harvest sweet potatoes on a farm near Turlock, Calif., on October 26, 2018.

Credit: Mario Tama Getty Images

Community action

Two hands grasp a heart on a billboard outside the church for refugees, beside a Bible quotation from Leviticus: “You shall love the foreigner as yourself.” People drive slowly past it all afternoon as they head to a car park and wait for a test from a health worker who will slide a swab far into their nostril.

Kenny Banh, an emergency-medicine physician at UCSF Fresno, paces excitedly around the transformed church in medical scrubs, reinvigorated by a chance to help people who are healthy enough to walk.

He explains that people of colour with COVID-19 were often the “sickest of the sickest” patients that he treated at the university hospital. A key problem contributing to higher death rates in this group is that they delay seeking help because they don’t have health insurance, can’t afford medical bills or fear doctors in the United States, he says.

“A lot of them don’t trust the medical community, and I don’t blame them in some respects because historically they haven’t been treated well.”

On the lawn outside the church, leaders of the Fresno COVID-19 Equity Project were training a legion of people with a knack for grasping the latest coronavirus news and relaying it to their neighbours.

The project hired and trained 110 of these community health workers, who together speak 16 different languages. That investment of time and money meant turning down researchers who had asked to join the project to study inequities, says Pacheco. She and her colleagues thought that community workers would have a higher pay-off in the near term, even if it cost them publications and grants down the road. What’s more, Banh adds, communities in the valley had grown exhausted with scientists surveying them year after year.

“By asking people questions, you give them a false belief that you’re going to deliver some sort of help,” he says; when change never arrives, people grow disillusioned.

Still, a century of neglect isn’t easily undone. Sparse neighbourhoods along the rural roads of the San Joaquin Valley can be traced back to temporary housing tracts built for migrant workers in the 1930s.

Today, some of these towns don’t have safe drinking water or a single clinic. And the city of Fresno itself is sharply divided. Predominantly Black, Latinx and Asian neighbourhoods are in the south of the city. These sections were shaded red on maps from the 1930s, indicating areas with large, non-white populations where banks were discouraged from issuing home loans.

Workers from Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas and Mexico harvest carrots in California in 1937.

This practice, known as redlining, pushed down property values in the areas, and helped to reinforce racial segregation and inequality. Although lawmakers attempted to mitigate the discriminatory practice in the 1960s, parts of south Fresno still have limited access to parks, Internet services, healthy food and other benefits.

According to the Central Valley Health Policy Institute, a child born in a wealthy neighbourhood in northern Fresno is expected to live past the age of 80—more than 10 years longer than a child born in parts of south Fresno, and 20 years longer than a child in rural neighbourhoods in the San Joaquin Valley, where average life expectancy is similar to that for many low-income countries.

Southwest Fresno is where Guadalupe Lopez lives with her husband and three children in a rented mobile home without drinkable tap water. By the time she connected with a community group serving Indigenous people from Mexico—Centro Binacional para el Desarrollo Indígena Oaxaqueño—she was facing eviction and eating barely a tortilla a day.

“It’s a nightmare,” she told me as we sat beside a bed and child-sized desk in her tidy living room. Just after garlic-picking season in late July, her 34-year-old husband developed a severe case of COVID-19. He gasped for air, but refused to go to a hospital because he was terrified by the possibility of being permanently separated from his family.

How would Lopez—who asked for her name to be changed because she’s an undocumented immigrant—care for their children without him?

But her husband agreed to see a doctor referred to him by a friend. The doctor sold Lopez injections of unapproved drugs that he said would help with COVID-19. She says the bill came to $1,500—all of the family’s savings.

In the ensuing weeks, her husband’s health deteriorated, and Lopez tested positive for the coronavirus, too. Neither of them could work in the fields, and their cupboard ran empty. She cries as she describes how her children became so thin that she could see the outlines of their ribs.

Lopez’s family was not eligible for federal funds to cover unemployment, and the state’s funds for sick leave had run dry. The Centro Binacional granted her money to cover rent. In October, Lopez’s husband returned to the fields, even though he still has bouts of intense fatigue.

Lopez’s eyes fill up again as she explains what it feels like to be an essential worker in a country that seems to want her dead. “When I go to the store covered in dust from working in the field, white people will look at me in disdain, even when I’m wearing a mask and they aren’t,” she says. “I feel awful because they look at us as less than human.”

Community health workers share similar stories of desperation. Although their intended role was to educate communities about the coronavirus and assist in contact tracing, they find themselves on phone calls at all hours, scrambling to find funds for parents who cannot feed their children or keep the lights on.

“I see so much sadness when I talk with people,” says Leticia Peréz de Trujillo, a community health worker with Cultiva La Salud, a Fresno-based health-equity advocacy organization involved in the COVID-19 Equity Project. Still, with guidance from this and other groups, around 1,000 people received grants that staved off hunger and homelessness—and the outreach probably prevented more than a few infections.

Part of the county’s infusion of coronavirus funds had been set aside for paid sick leave, and that assurance seemed to drive a rise in testing. In December, people were lining up for tests at the converted church before daylight, prompting the team to relocate to a larger spot. But the situation remained far from resolved.

As the coronavirus surged across the country over the holiday season, the San Joaquin Valley emerged as a hotspot. “This is driven by infections among our essential workers,” Arias tells me on a phone call in late December. Nearly 500 people had died of COVID-19 in the valley in that month alone.

“We’ve got huge outbreaks at meat-packing plants and at an Amazon distribution centre,” he says. “There’s no capacity in hospitals, and we’re bringing in freezer trailers meant for produce to store bodies, because we’ve run out of space in the morgue.”

Political limits

By the end of last year, initiatives such as the COVID-19 Equity Project in Fresno had cropped up across the United States. These programmes are now spearheading equitable vaccine distribution. But the projects are funded by short-term infusions of money. When that dries up, much of the work towards eliminating health disparities will fall back on the health system, says Banh.

But unlike grass-roots groups, officials in the US public-health system—comprising the CDC and health departments across the country—tend to avoid politically sensitive topics, such as calling for higher wages and immigration reform.

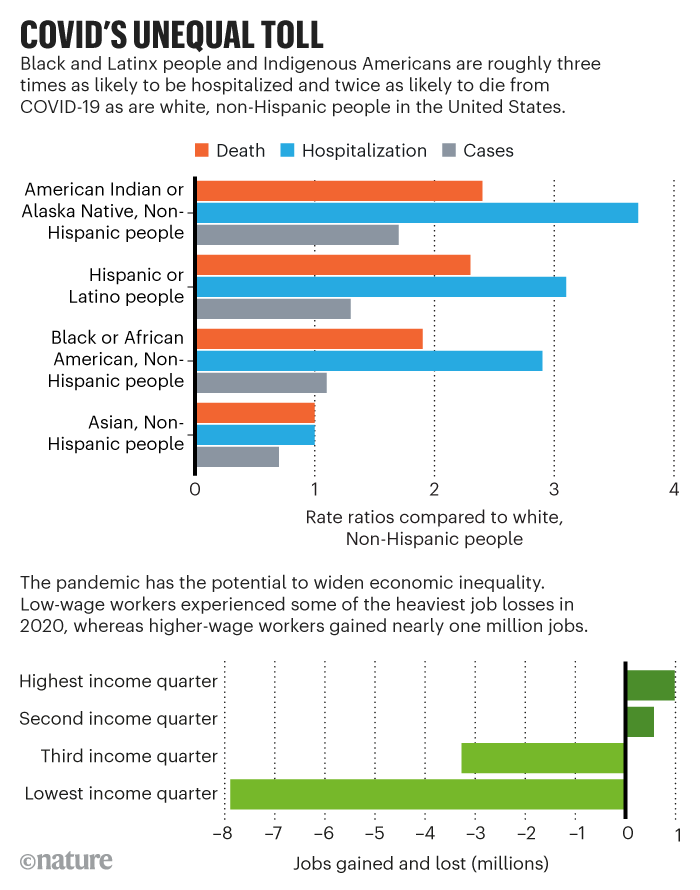

Government researchers have identified the social determinants of health during the pandemic, but they’re typically treated as immutable factors. For example, an October 2020 investigation in the CDC’s journal, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, finds that Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately dying of COVID-19, possibly because of underlying diseases, dense households, in-person work, poor access to health care and discrimination (see also ‘COVID’s unequal toll’).

Credit: Nature

But instead of suggesting affordable housing, universal health care and labour protections, the report recommended masks, hand washing and social distancing.

Another CDC study posted online on 12 April finds that COVID-19 hospitalizations were highest for Hispanic or Latinx people in the United States, compared with other racial or ethnic groups. The authors attribute the disparity to the social determinants of health, and recommend that health departments distribute vaccines accordingly. But they don’t suggest ways to correct the underlying problems.

Ronald Labonté, a public-health researcher at the University of Ottawa in Canada, isn’t surprised to see government scientists dodging political flashpoints, because there can be severe consequences for speaking out—some have received death threats, for instance. Similarly, he says, public-health researchers often link poverty and marginalization to disease, but don’t challenge the status quo by digging deeper into why people are poor or marginalized in the first place.

“What drives it is essentially oppression, exploitation and the pursuit of power and profit,” he says. “But I don’t think you’re gonna have too many public-health departments come out and say that.”

This doesn’t mean that people in the public-health system don’t want to address systemic injustice. One obstacle is that health departments have limited control. For example, Fuller at Fresno’s health department says he can advise companies on best COVID-19 practices, but the department can’t enforce rules. “The safety and health of employees is not under our jurisdiction.”

Indeed, that duty typically falls to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the US regulatory agency with the power to inspect workplaces to ensure that conditions are safe.

But if public health has been underfunded, OSHA’s resources are even more scant, and its powers are consistently undermined by business interests, says epidemiologist David Michaels at the George Washington University School of Public Health in Washington DC, who directed OSHA under former president Barack Obama. Last year, the number of OSHA workplace safety inspectors was lower than at any time in the past 45 years, according to the National Employment Law Project.

Perhaps this is why so few of more than 13,000 complaints to OSHA about coronavirus-related hazards were followed up with inspections and fines. “We have structured our economy so that many workers have few rights, and are underpaid, and face hazards that would be unacceptable to the corporate leaders who profit from their work,” Michaels says.

Singh’s mother lives that reality. Two weeks before she tested positive for the coronavirus at the Foster Farms meat-packing plant, she told her son that 140 people at work might have COVID-19. The factory floor looked emptier, she told him, and a flyer in English on the notice board included the number 140.

Singh didn’t know what to make of his mother’s fears. “I feel like everyone I know at Foster Farms speaks Spanish, Hmong and Punjabi, and like very few speak English,” he explains. He told his mother to ask a co-worker with a smartphone to photograph the sign, and send it to him to read. But her colleague refused because she didn’t want to get into trouble.

A couple of days later, she said the sign had disappeared—but the outbreak was silently growing larger. In December, the United Farm Workers of America union sued Foster Farms on behalf of several employees from a plant in Livingston, alleging that “Foster Farms has failed to take the necessary safety precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19”.

In fact, Foster Farms’ Livingston plant is exceptional because it is one of very few agricultural businesses shut down by health-department officials for a COVID-19 outbreak.

Salvador Sandoval, an officer at the Merced health department—where Livingston is located—became upset when he found out that two employees had died at the plant in July. That prompted the department to request a list of all worker infections. “Buried in it were more people who were deceased,” Sandoval says.

He and the department’s epidemiologist were alarmed. They wanted to shut the Livingston plant until everyone could be tested. So they reached out to California’s health department and the state’s OSHA office for help as Merced’s leaders pushed back against the closure.

The health department even got a call from a federal official in mid-August, saying that the plant must remain open because of Trump’s executive order to keep meat-processing plants operational.

But Merced’s tiny department persisted. At the end of August, after eight workers had died, the Livingston plant partially closed for six days so that it could be cleaned, and workers tested. “It wasn’t easy,” Sandoval says. “This was blood, sweat and tears.”

In a statement to Nature, Foster Farms writes that the company is committed to the health and welfare of its employees, and that it has implemented COVID-19 protective measures throughout the pandemic, including an extensive testing system.

In February, the company began vaccinating California employees. And as for specific complaints from workers, the company writes, “Since March 2020, all company employees have been encouraged to share any concerns about their health and safety regarding COVID-19 with their supervisors.”

Protecting public health

Evidence on the toll of outbreaks at meat-packing plants has been undeniable. In a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers estimated that, in just the first half of 2020, up to 310,000 cases and as many as 5,200 deaths in the United States were due to outbreaks at livestock plants that spread through surrounding communities.

And those figures point to a larger problem. Public-health specialists are correct in saying that they don’t have control of workplaces, but when they can’t successfully push back against policies that favour corporate interests, historians say the field can’t accomplish one of its core functions—protecting the most vulnerable from disease.

“We know what the impact is of a lack of employment, a lack of fair wages, a lack of transport, of poor education and racism,” says Graham Mooney, a public-health historian at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “So, if public health has no power to influence these issues, then public health becomes nothing.”

Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, agrees. He adds that the time to push for social and economic changes is now, when the tragedies of the pandemic have laid bare an urgent need for reform. He recalls how the devastation of the Great Depression in the 1930s led to the ‘New Deal’, a series of programmes that included unemployment insurance, housing reform and welfare benefits under former president Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“Once again, we need to come up with a new social compact for America,” says Benjamin. “One that says that everyone should have access to a living wage, to affordable housing, to affordable health care, that our environment should be safe.”

A month after I talked to Benjamin, US President Joe Biden proposed a $2-trillion economic plan that includes features reminiscent of the New Deal. It even echoes Virchow’s report on curbing typhus in Upper Silesia in the 1850s, with calls for higher wages, improved working conditions, public schools and affordable housing—paid for, in part, through tax increases on corporations. If enacted, proponents say, the plan could reverse 40 years of rising inequality in the United States.

On 31 March, the American Public Health Association released a statement in favour of Biden’s proposal, calling it essential to addressing disparities in health.

Other scientists are getting political, too. When I asked Fauci to elaborate on statements he’s made about the social determinants of health, he said that disparities are rooted in systemic racism and economic inequality, and that it’s time to discuss them.

“As scientists,” he says, “we have a societal responsibility to talk about this—we’re the ones in the trenches taking care of people, and analysing the data on disparities first-hand.”

The authors of the Lancet report on US health problems were more prescriptive. They listed solutions, such as higher wages and immigration reform. They also elaborated on how researchers might push for these policies by framing arguments to attract broad support, using hashtags on social media and forming unusual coalitions, such as with activist groups.

Planey, the medical geographer, says that academics could learn how to write memos that politicians can understand in three minutes. To get more traction, they should consider the costs of the solutions they propose, as well as the benefits. “People think, ‘If I produce good evidence, people will listen,’ but that isn’t how it works,” she says.

Whether the public-health field can become more radical and outspoken in demanding policy changes remains to be seen. Several early-career researchers told me they’ve been advised not to speak publicly on charged political topics until they have tenured positions.

But the status quo won’t help Singh and his family. Their financial stress worsened after his mother left her job in March. “Ever since she had COVID, she’s felt fatigued and not able to stand for the long hours required,” Singh explains. She also has chronic neck and back pain after years of factory labour. The family has received temporary assistance: food stamps to subsidize the cost of groceries, and a month’s rent was covered by the Jakara Movement, a group in Fresno’s COVID Equity Project.

In his graduate programme at one of the leading public-health schools in the country, Singh’s lectures cover the links between poverty and other socio-economic factors and disease. He’s begun to find it frustrating. “There’s a lot of research about health disparities and inequities,” he says. “But what are we doing to eradicate or even reduce them?” He suggests that researchers partner with community organizations that have been advocating for marginalized people. “Publishing another paper saying workers are at higher risk of COVID isn’t solving the problem,” he says. “Don’t you want to prevent that from happening?”

This piece was supported by grants from the Pulitzer Center and the MIT Knight Science Journalism fellowship.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on April 28, 2021.